One of Lydia Breed’s woodcuts titled Beethoven and Bruckner, circa 1964. Courtesy of the Lynn Museum.

The Legacy of Lydia Breed

This story originally appeared in the 2022 Summer edition of the 01907 Magazine

If you were to pull out your phone or computer and Google the name Lydia Breed, the first thing that would populate on your screen would likely be an amalgamation of photos of strange looking dogs.

If you scroll a little further down the page, you might see an obituary describing a woman who was born in Lynn, but mainly resided in Swampscott. You might even learn a little bit about her life from the Lynn Museum’s website if you dug deep enough.

But, what you won’t see, and what you likely may have never seen until reading this article, is the beautiful world of colors and lines that Lydia Breed created in her lifetime as a printmaker in Swampscott.

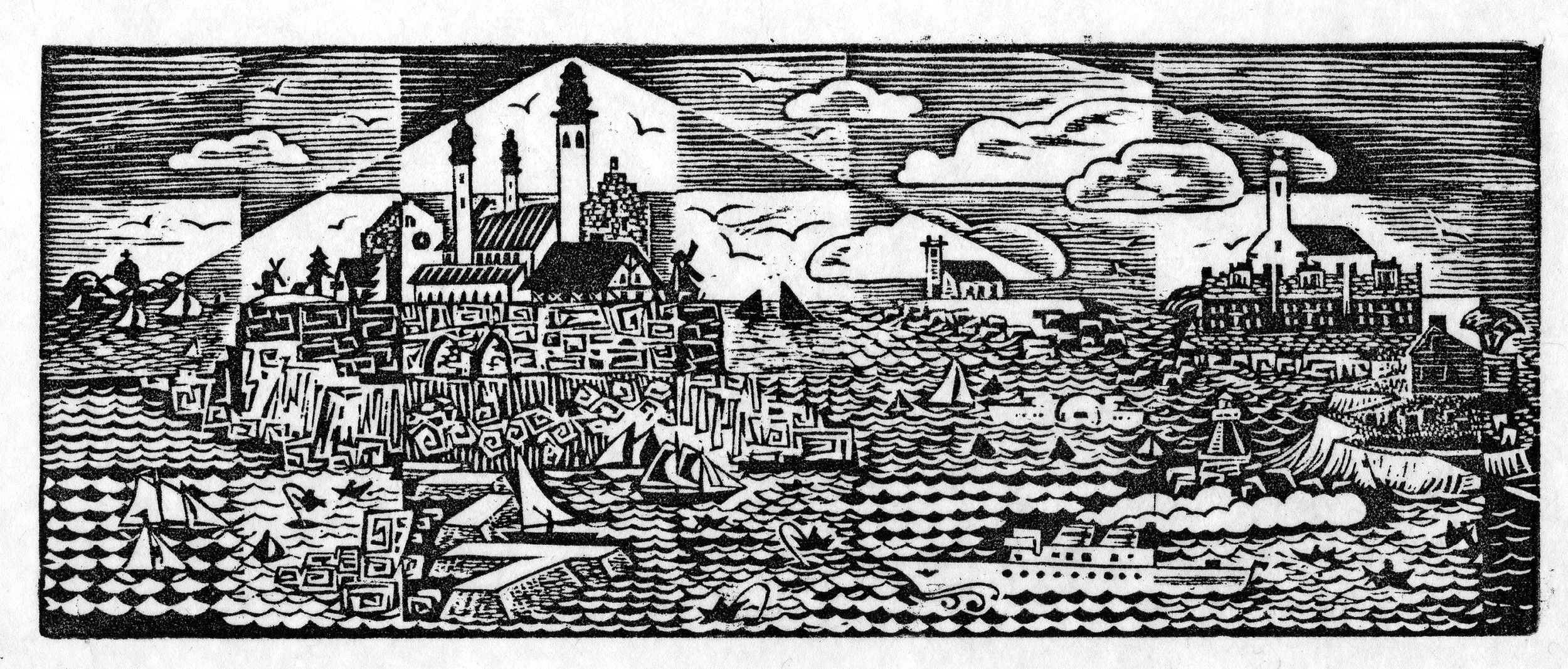

Top: Lydia Breed’s color woodcut titled Motif #2 Rockport, circa 1958.

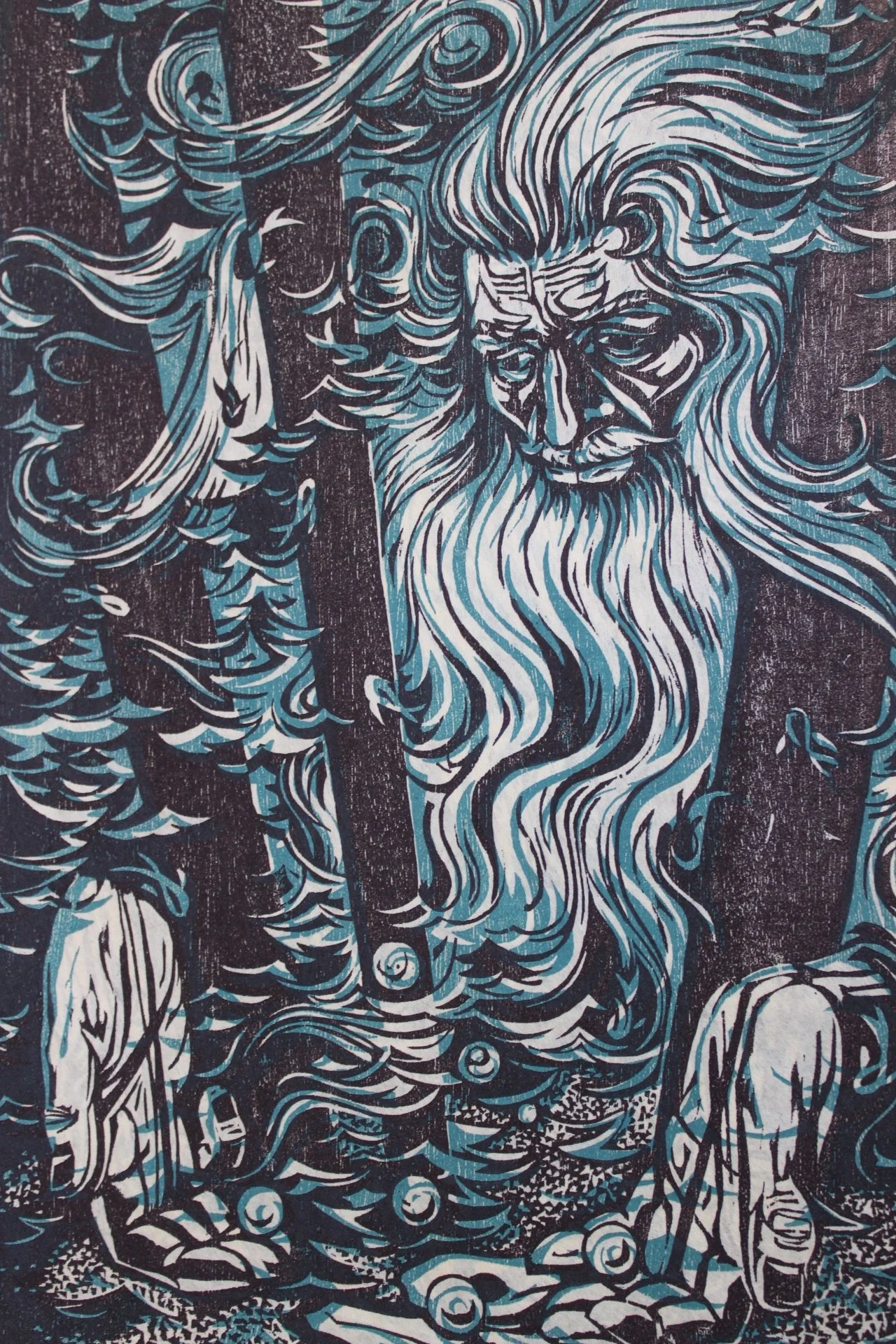

Right: Lydia Breed’s color woodcut titled Neptune, circa 1959.

Bottom: Lydia Breed’s woodcut titled Mothers Island circa 1959.

Landscapes, religious depictions, expressions of activism, Lydia did them all with a distinct stroke that would come to define the era of art in Boston during the 1950s.

“Lydia was part of a movement in Boston. By the 1940s, Boston was starting to have a voice in the Art History landscape,” said Renee Covalucci, the current president of The Boston Printmakers.

“New York went completely abstract and Boston stayed with subject matters, figuration, and there was a group called the Boston Figurative expressionists. Lydia followed the philosophy of them pretty purely in the way she develops her prints. She abstracts them a little … she adds emotion, she adds tension, she adds expressive elements that make it feel like it sparkles. She really represents that philosophy really well.”

Born in September 1925, Lydia would enter a family of dynasty status as a distant relative of Allen Breed who helped settle Lynn when he sailed across the Atlantic Ocean in 1630. Like those before her, Lydia would go on to live a life of service to her communities as an active member of multiple organizations such as the Lynn Historical Society, Friends of Lynn Woods, and the Unitarian Universalist Church of Greater Lynn.

The early years of her life strolling the coasts of Swampscott and the woods of Lynn proved to be formative to the genius of work that would come after graduating from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in 1947. That same year she would go on to become a founding member of the Boston Printmakers where she would refine her craft of printmaking with wood cuts.

A trip to Japan would serve as a source of inspiration for beautiful landscapes of mountain peaks and trees that she would go on to create, but more importantly, it’s where she learned more advanced techniques of wood-cut printmaking.

She would go on to bring these talents and skills back to the North Shore where she would depict contemporary scenes of her surroundings such as the Marblehead Festival, where she shows a crowd enamored by the sharp sounds of a guitar player.

While her preliminary works tended to lean toward painting the scenes around her, her later works focused more on the emotion and story that can be told through a print. Lydia didn’t shy away from expressing her views on the ever-changing society swirling around her in the heat of the Civil Rights Movement in the 50s and 60s, when she flourished as an artist.

“I would consider Lydia an activist through her work. She definitely had commentary on social issues and was pretty progessive and she reflected that in her church community as well,” said Doneeca Thurston, executive director of the Lynn Museum, where 46 prints of Lydia’s are currently on display.

Standing out amongst her work at the museum is an untitled piece, which reads: “Oh Lord, We’ll Join Hand in Hand, Hand in Hand We’ll Join, Hand in Hand Someday, We’ll Join Hand in Hand. The words are interweaved between hands that are trying to connect but are blocked by chains.

To Thurston, “It feels very timeless, very relevant especially in today’s climate. I find that these hands are trying to join one another but there are these chains getting in the way and the question of will we ever be able to join hand in hand one day, will we ever be able to achieve that. Especially in light of issues of police brutality, racial injustice, systemic racism, the list goes on, but I just feel like this piece is timeless unfortunately.”

Covalucci, who presides over the latest generation of Boston printmakers and helped curate the current exhibit at the museum, notes the emotion in Lydia’s work is the driving force behind what most modern viewers of her work discuss.

“She was a thinker. You can’t talk about any of [her work] without understanding how deeply she felt and how much meaning she put in her art and that's why I think people come to the show and look at it and say ‘I feel something, I see something, it’s communicating to me.’”

Covalucci also agrees with Thurston’s assessment of Lydia’s expression, noting that part of the Boston movement was to “be truthful, be active, show people truthful things, break down the common beliefs or universal beliefs and look more deeply in and see what's happening to people.”

Toward the latter years of her career, Lydia put down her gouges and ceased a majority of her printmaking and instead turned to wood sculpture carving. Her most notable sculpture titled “7 Days” was a gift to the Unitarian Universalist Church community which helped shape her beliefs and moral compass her entire life.

The original church of the Unitarian Universalist Church in Lynn burnt down early in the month of January in 1977 and Lydia took it upon herself to save as much of the wood from the pews and other parts of the building and she repurposed them into sculpture which is still on display at the Unitarian Universalist Church in Swampscott.

While she lived a long and fruitful life, dying at the age of 94 in December 2019, her life and body of work is largely enigmatic to those who don’t reside in the 01907 zip code.

Sammia Atoui, founder of the MiraMar Print Lab on Humphrey Street was unaware of Lydia’s work before being introduced to her by Covalucci, despite Atoui using some of the very same techniques in her work.

“She’s ahead of my time but not by that much, we were living in the same area at the same time even if she wasn’t working at that point. She’s a contemporary to all of us,” said Atoui. “I’m a transplant here, so it’s just really interesting to have this person who is doing amazing work right in your backyard and it took this for me to be able to see this.”

Even though Atoui herself creates wood-cut and linoleum prints, she chalks up her lack of knowledge of Lydia’s life and work to the fact that her presence online is minimal, to put it lightly. “Living in the day of the internet, it feels like if you're not on the internet you don't exist” said Atoui.

However, not all hope is lost for preserving Lydia’s legacy. Part of the Lynn Museum’s prerogative in having a wide-ranging exhibition of Lydia’s work on display is to help create awareness for the native’s incredible prints.

On June 17th, the museum is hosting an event which they hope will draw a large swath of the residents that knew Lydia in an attempt to tell a more complete story of her life which they will then use to create a Wikipedia page for Lydia.

This page, they hope, will allow prospective admirers to discover her pristine prints when they search for her, rather than puffy pooches.

However, until that day, the memory of Lydia Breed, and the life that she left behind, lives on in the memories of those that knew her, and the intricate wood-carved slabs that built her legacy.